Impact of glucocorticoids on clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer

-

摘要:目的

评估糖皮质激素(GC)对免疫检查点抑制剂(ICI)治疗晚期非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)临床效果的影响。

方法回顾性分析扬州大学附属医院接受ICI治疗的131例晚期NSCLC患者的临床资料,根据患者在ICI治疗前后3个月内是否使用GC类药物(≥10 mg/d泼尼松或等效GC)分为GC组(n=79)与Non-GC组(n=52)。GC组根据GC用途不同分为非肿瘤症状相关组、肿瘤症状相关组、免疫相关不良事件(irAEs)组及化疗前预处理组。分析GC使用与患者一般临床特征的相关性。采用Kaplan-Meier生存曲线分析GC使用对患者总生存期(OS)及无进展生存期(PFS)的影响。采用单因素和多因素Cox风险比例回归模型分析GC使用是否为NSCLC患者预后的影响因素。

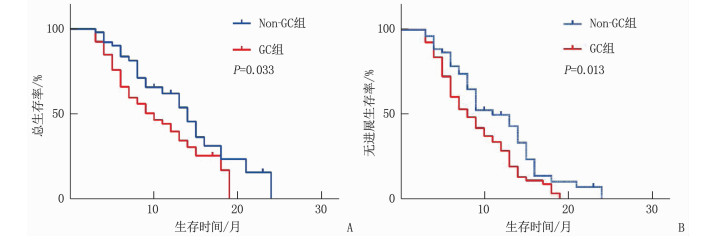

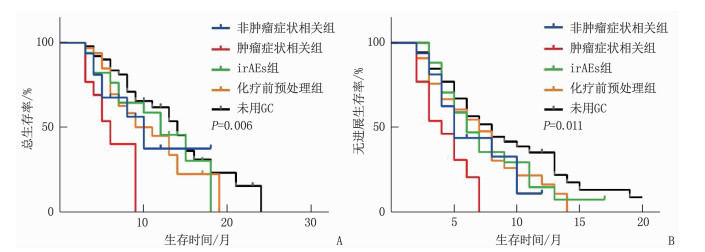

结果卡方检验分析显示,GC使用与患者年龄(χ2=0.180,P=0.672)、性别(χ2=3.179,P=0.075)、吸烟(χ2=0.579,P=0.447)、病理类型(χ2=0.628,P=0.428)、美国东部肿瘤协作组(ECOG)评分(χ2=0.074,P=0.785)、治疗线数(χ2=1.853,P=0.173)无相关性,与治疗策略有相关性(χ2=3.998,P=0.046)。GC组的OS及PFS短于Non-GC组,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。多因素Cox回归分析显示,使用GC是晚期NSCLC免疫治疗患者OS(HR=1.82,P=0.026)和PFS(HR=1.76,P=0.012)的独立影响因素。亚组分析表明,相比于非肿瘤相关症状、irAEs、预处理,肿瘤相关症状患者采用GC治疗的OS(P=0.006)及PFS(P=0.011)较短。多因素Cox回归分析表明,GC用于治疗肿瘤相关症状是影响ICI治疗晚期NSCLC患者OS(P=0.001)及PFS(P=0.005)的独立危险因素。

结论GC的使用与ICI治疗晚期NSCLC的临床疗效呈负相关,特别是GC用于肿瘤相关症状时ICI疗效明显降低,因此接受ICI治疗的晚期NSCLC患者应慎重使用GC。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo evaluate the impact of glucocorticoids (GC) on the clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in treating non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

MethodsThe clinical data of 131 patients with advanced NSCLC who received ICI treatment in the Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University were retrospectively analyzed. They were divided into GC group (n=79) and non-GC group (n=52) according to whether they used GC (≥ 10 mg/d prednisone or equivalent GC) within 3 months before and after ICI treatment or not. The GC group was divided into four subgroups according to the following indications: non-cancer indications group, cancer indications group, immune related adverse events (irAEs) group and pre-chemotherapy treatment group. The correlation between GC usage and the clinical characteristics of patients was analyzed. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to analyze the impact of GC use on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). The univariate and multivariate analysis based on Cox hazard proportional regression models were used to identify whether GC use was a prognostic factor.

ResultsNo significant correlations were found between GC use and age (χ2=0.180, P=0.672), gender (χ2=3.179, P=0.075), smoking (χ2=0.579, P=0.447), pathological type (χ2=0.628, P=0.428), the score of United States Eastern Collaborative Group(ECOG) (χ2=0.074, P=0.785) score and treatment lines (χ2=1.853, P=0.173), while it was correlated with treatment strategies (χ2=3.998, P=0.046). The OS and PFS of the GC group were shorter when compared with the non-GC group, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The multivariate analysis showed that GC use was an independent influencing factor for OS (HR=1.82, P=0.026) and PFS (HR=1.76, P=0.012). The subgroup analysis demonstrated that patients receiving GC for cancer related indications had shorter OS (P=0.006) and PFS (P=0.011) than those receiving GC for non-cancer indications, irAEs, and pre-chemotherapy treatment. The multivariate analysis showed that GC use for cancer related indications was an independent risk factor for OS (P=0.001) and PFS (P=0.005).

ConclusionThe GC use is negatively correlated with the clinical efficacy of ICI in treating patients with advanced NSCLC, especially for those receiving GC for cancer-related indications. GC should be used cautiously in ICI-treated NSCLC patients.

-

股骨粗隆间骨折属于老年群体常见骨折类型,与骨质疏松症有关,具有治疗难度大、恢复时间长等特点,严重威胁老年患者的生活质量,需要及时予以手术治疗[1-2]。内固定术是针对该类骨折的最有效术式,但对于内固定物种类的选择,尤其是在股骨近端防旋锁定钉内固定术(PFNA)与锁定钢板内固定术的选择上,临床上存在较大的争议。本研究比较PFNA与锁定钢板内固定治疗老年股骨粗隆间骨折的疗效,现报告如下。

1. 资料与方法

1.1 一般资料

将2012年1月—2017年1月收治的90例老年股骨粗隆间骨折患者随机分为2组,每组45例。本研究经本院医学委员会认可,患者签署知情同意书。所有患者均经影像学检测确诊。纳入标准: ① 60~85岁老年患者; ②符合内固定指征且不存在手术禁忌证患者; ③临床资料齐全且不存在远期失访风险患者等。排除标准[3-4]: ①病理性或陈旧性骨折患者; ②合并严重内科疾病患者; ③近6个月心血管意外发作史患者等。PFNA组患者男21例,女24例,年龄60~82岁,平均(72.10±6.00)岁,摔伤26例,交通伤19例; 锁定钢板组患者男23例,女22例,年龄61~84岁,平均(71.80±6.30)岁,摔伤29例,交通伤16例。2组患者性别、年龄与骨折原因等一般资料比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05), 具有可比性。

1.2 方法

PFNA组患者给予PFNA术,即将患者全麻后取仰卧位并固定于骨科牵引床,双下肢固定后做患侧肢体牵引, C型臂X线视野下骨折闭合复位; 粗隆顶点皮肤投影处做长约4 cm的纵行切口,股骨大粗隆顶点偏内侧中前方1/3处放置开口器,导针引入髓腔并扩髓,置入对应PFNA髓内钉; 骨折近端另做一小切口,以瞄准器为准,置入螺旋刀片导针与旋紧螺钉; 骨折远端再做一小切口,以钉头至股骨头关节面软骨下0.5 cm置入防旋螺钉,固定满意后冲洗术区并缝合。

锁定钢板组患者则给予锁定钢板内固定术,即患者全身麻醉后取仰卧位,于大粗隆与远端外侧分别做切口,分离、暴露骨折端,C型臂X线视野下骨折闭合复位; 以对应解剖钢板在近端以克式针临时固定,并拧入锁定螺钉,X线机观察颈干角与螺钉的相对位置,股骨颈头部固定钢板处拧入拉力螺钉,远端则置入皮质骨髓钉,固定满意后冲洗术区并缝合。

1.3 检测方法

比较2组患者围术期指标,包括手术时间、切口长度、术中失血量、术后引流量、下地时间与骨折愈合时间等[5-6]。比较2组并发症发生情况,主要为褥疮、肺栓塞、下肢静脉血栓、内固定断裂、髋内翻与螺钉切出等。髋关节功能参考Harris髋关节功能评分标准,包括疼痛、功能与活动范围3个维度,并计算总分,分数越高代表髋关节功能越佳。预后效果参考简易生活质量量表(SF-36), 包括生理功能、角色限制、躯体疼痛等8个维度,评分越高代表该维度生活质量越高。

1.4 统计学分析

采用IBM公司SPSS 19.0软件分析全部数据。围术期指标、Harris评分与远期预后等计量资料采用均数±标准差表示,采用单独或重复测量t检验,并发症等计数资料采用[n(%)]表示,采用卡方检验, P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 2组患者围术期指标与并发症比较

PFNA组患者手术时间、切口长度、术中失血量、术后引流量、下地时间与骨折愈合时间均显著优于锁定钢板组(P < 0.01); 2组患者各类并发症发生率无显著差异(P>0.05), 但PFNA组患者总并发症发生率显著低于锁定钢板组(P < 0.05)。见表 1。

表 1 2组患者围术期指标与并发症比较(x±s)[n(%)]指标 PFNA组(n=45) 锁定钢板组(n=45) 围术期指标 手术时间/min 59.41±8.33** 96.20±14.89 切口长度/cm 8.13±1.06** 16.47±5.17 术中失血量/mL 150.79±25.98** 361.70±40.48 术后引流量/mL 80.25±11.25** 223.67±38.93 下地时间/d 6.56±1.02** 25.13±5.82 骨折愈合时间/周 12.30±2.16** 14.75±2.37 并发症 褥疮 1(2.22) 4(8.89) 肺栓塞 0 1(2.22) 下肢静脉血栓 1(2.22) 2(4.44) 内固定断裂 0 1(2.22) 髋内翻 0 1(2.22) 螺钉切出 0 1(2.22) 合计 2(4.44)* 10(22.22) 与锁定钢板组比较, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01。 2.2 2组患者治疗后Harris评分比较

2组患者治疗后3个月疼痛、功能与活动范围各维度生活质量评分比较无显著差异(P>0.05)。PFNA组患者末期随访Harris总分显著高于锁定钢板组(P < 0.01)。见表 2。

表 2 2组患者治疗后Harris评分比较(x±s)分 指标 PFNA组(n=45) 锁定钢板组(n=45) 治疗后3个月 末期随访 治疗后3个月 末期随访 疼痛 28.04±4.17 24.37±3.86**## 27.85±4.28 20.06±3.89** 功能 楼梯 2.37±0.50 2.28±0.50 2.41±0.49 2.31±0.48 交通 0.72±0.10 0.68±0.10 0.75±0.12 0.67±0.11 坐立 3.82±0.44 3.72±0.49**## 3.85±0.41 3.30±0.42** 鞋袜 2.48±0.43 2.41±0.53 2.51±0.45 2.30±0.50 步态 9.40±0.89 9.13±0.97**## 9.42±1.02 7.12±0.87** 行走辅助 8.30±0.91 8.05±0.88**## 8.32±0.93 6.02±0.79** 距离 8.83±0.96 8.72±0.96**## 8.90±0.95 6.18±0.72** 畸形 2.81±0.80 2.48±0.70 2.89±0.81 2.58±0.73 活动范围 前屈 3.66±0.72 3.40±0.65 3.59±0.69 3.33±0.62 外展 3.50±0.69 3.37±0.68 3.49±0.70 3.41±0.70 伸展外旋 3.40±0.72 3.30±0.70 3.42±0.71 3.25±0.74 伸展内旋 3.19±0.68 3.02±0.62 3.15±0.72 3.12±0.60 内收 4.12±0.52 3.72±0.59 4.09±0.60 3.69±0.53 合计 85.11±7.01 80.89±7.02**## 84.90±7.23 71.36±6.75** 与治疗后3个月比较, **P < 0.01; 与锁定钢板组比较, ##P < 0.01。 2.3 2组患者远期预后比较

2组患者治疗前生理功能、角色限制、躯体疼痛等各维度生活质量评分比较无显著差异(P>0.05)。PFNA组患者末期随访生理功能、躯体疼痛与总体健康评分均显著高于锁定钢板组(P < 0.01)。见表 3。

表 3 2组患者远期预后比较(x±s)分 指标 PFNA组(n=45) 锁定钢板组(n=45) 治疗前 末期随访 治疗前 末期随访 生理功能 41.80±7.13 62.08±7.75**## 41.06±7.04 51.96±7.21** 角色限制 50.45±7.59 71.32±8.06** 51.12±7.60 69.38±7.84** 躯体疼痛 36.12±6.56 61.25±7.62**## 36.09±6.75 50.43±7.50** 总体健康 50.04±7.35 71.36±7.40**## 50.50±7.09 62.57±7.29** 活力 53.35±8.04 75.23±9.15** 52.88±8.16 73.83±9.38** 社会功能 61.43±9.50 88.24±11.77** 61.50±10.13 85.49±11.86** 情感职能 50.50±8.77 62.60±9.14** 50.12±8.66 60.04±9.27** 精神健康 61.48±9.33 80.05±11.04** 60.93±10.20 77.88±10.93** 与治疗前比较, **P < 0.01; 与锁定钢板组比较, ##P < 0.01。 3. 讨论

股骨粗隆位于股骨大粗隆与小粗隆之间,主要由松骨质构成,并由旋股外侧动脉与内侧动脉供应血供,是骨折高发部位,约占全部骨折的3%~4%, 好发于60岁以上老年群体,病死率高达15%~20%, 严重威胁老年患者的生命健康与生活质量[7-8]。老年群体较为特殊,其身体状况相对较差,常伴有多重基础疾病,骨折后的并发症会导致患者长期卧床而加重病情。非手术治疗时间较长,不利于早期康复训练,而手术治疗可第一时间复位骨折端,并尽早进行早期功能训练,恢复骨折功能,从而大幅度降低病死率[9-10]。

内固定术是股骨粗隆间骨折的最有效治疗方案,其中以锁定钢板内固定术最为普遍,是以解剖型锁定钢板作为内固定材料进行固定,采用多点固定达到完全复位的效果,可充分减少骨膜的剥离程度,易于稳定骨折断端,具有较强的支撑力与抗旋转作用,并且对周围血供的影响不大,有利于伤口与骨折端的愈合,但其力臂较长,产生的力学缺陷易造成钢板断裂,固定持久性欠佳,不利于术后早期负重[11-12]。

PFNA具有创伤低、血运影响小、恢复快等优点,其长尖端与凹槽可避免局部应力的集中,使插入难度大幅降低,有效控制迟发型股骨干骨折[13-16]。螺旋刀片具有稳定的支持力与抗旋转能力,术中不需要扩髓,可避免骨量的流失,减少并发症的发生,更有益于存在骨质疏松症的老年群体,更加符合生物力学原理[17-20]。

本研究结果显示, PFNA组患者手术时间、切口长度、术中失血量、术后引流量、下地时间与骨折愈合时间均显著优于锁定钢板组,充分说明PFNA不仅大幅度降低手术创伤,减少血运的损伤,并能缩短恢复时间,提高治疗效率[21-23]。PFNA组末期随访时Harris总分、生理功能、躯体疼痛与总体健康评分显著高于锁定钢板组,充分说明PFNA更适合老年人群,并能有效控制迟发型股骨干骨折,有效改善患者的预后,尤其在骨折后生理功能与疼痛方面效果更为显著。PFNA组总并发症发生率明显低于锁定钢板组,充分说明PFNA创伤小,不需要扩髓,其骨量流失的减少可降低术后并发症发生率,安全性更高[24-26]。

综上所述,相比于锁定钢板内固定术, PFNA具有创伤低、恢复快、并发症少等优势,对髋关节的治疗与远期预后效果更佳。

-

表 1 131例接受ICI治疗的晚期NSCLC患者一般临床资料比较[n(%)]

临床特征 分类 例数 Non-GC组(n=52) GC组(n=79) χ2 P 年龄 ≤65岁 50 21(40.4) 29(36.7) 0.180 0.672 >65岁 81 31(59.6) 50(63.3) 性别 女 25 6(11.5) 19(24.1) 3.179 0.075 男 106 46(88.5) 60(75.9) 吸烟 从不 48 17(32.7) 31(39.2) 0.579 0.447 曾经/现在 83 35 48(60.8) 病理类型 非鳞癌 70 30(57.7) 40(50.6) 0.628 0.428 鳞癌 61 22(42.3) 39(49.4) ECOG评分 0~1分 94 38(73.1) 56(70.9) 0.074 0.785 2~3分 37 14(26.9) 23(29.1) 治疗策略 单药 18 11(21.2) 7(8.9) 3.998 0.046 联合 113 41(78.8) 72(91.1) 治疗线数 一线治疗 47 15(28.8) 32(40.5) 1.853 0.173 二线治疗及以上 84 37(71.2) 47(59.5) ECOG: 美国东部肿瘤协作组。 表 2 131例接受ICI治疗的晚期NSCLC患者OS的单因素及多因素分析

变量 参照 单因素 多因素 HR 95%CI P HR 95%CI P 年龄 ≤65岁 1.17 0.72~1.90 0.531 1.14 0.68~1.92 0.620 性别 女 1.23 0.67~2.26 0.502 1.28 0.67~2.48 0.457 吸烟 无 1.34 0.82~2.19 0.250 1.40 0.80~2.43 0.239 病理类型 非鳞癌 1.18 0.74~1.88 0.498 1.07 0.65~1.77 0.781 ECOG评分 0~1分 1.73 1.04~2.88 0.037 1.44 0.83~2.53 0.199 治疗策略 单药 1.02 0.49~2.13 0.966 0.91 0.41~2.05 0.828 治疗线数 一线 1.30 0.79~2.16 0.303 1.33 0.75~2.35 0.328 激素使用 否 1.68 1.02~2.76 0.043 1.82 1.07~3.08 0.026 表 3 131例接受ICI治疗的晚期NSCLC患者PFS的单因素及多因素分析

变量 参照 单因素 多因素 HR 95%CI P HR 95%CI P 年龄 ≤65岁 1.17 0.78~1.75 0.462 1.22 0.79~1.87 0.376 性别 女 0.97 0.59~1.59 0.902 0.98 0.57~1.70 0.952 吸烟 无 1.21 0.81~1.83 0.353 1.46 0.90~2.35 0.126 病理类型 非鳞癌 1.08 0.73~1.60 0.713 0.95 0.62~1.47 0.832 ECOG评分 0~1分 1.49 0.97~2.27 0.066 1.22 0.77~1.95 0.400 治疗策略 单药 0.68 0.40~1.17 0.161 0.60 0.33~1.09 0.093 治疗线数 一线 1.38 0.90~2.11 0.138 1.30 0.80~2.13 0.291 激素使用 否 1.58 1.04~2.40 0.031 1.76 1.13~2.74 0.012 表 4 GC组接受ICI治疗的晚期NSCLC患者一般临床资料比较[n(%)]

临床特征 分类 GC组(n=79) 非肿瘤症状相关组(n=16) 肿瘤症状相关组(n=13) irAEs组(n=17) 化疗前预处理组(n=33) χ2 P 年龄 ≤65岁 29(36.7) 2(12.5) 7(53.8) 8(47.1) 12(36.4) 6.638 0.082 >65岁 50(63.3) 14(87.5) 6(46.2) 9(52.9) 21(63.6) 性别 女 19(24.1) 2(12.5) 4(30.8) 3(17.6) 10(30.3) 2.484 0.493 男 60(75.9) 14(87.5) 9(69.2) 14(82.4) 23(69.7) 吸烟 从不 31(39.2) 3(18.8) 5(38.5) 10(58.8) 13(39.4) 5.556 0.135 曾经/现在 48(60.8) 13(81.3) 8(61.5) 7(41.2) 20(60.6) 病理类型 非鳞癌 40(50.6) 8(50.0) 6(46.2) 8(47.1) 18(54.5) 0.396 0.941 鳞癌 39(49.4) 8(50.0) 7(53.8) 9(52.9) 15(45.5) ECOG评分 0~1分 56(70.9) 10(62.5) 8(61.5) 12(70.6) 26(78.8) 2.293 0.506 2~3分 23(29.1) 6(37.5) 5(38.5) 5(29.4) 7(21.2) 治疗策略 单药 7(8.9) 2(12.5) 3(23.1) 2(11.8) 0 7.600 0.024 联合 72(91.1) 14(87.5) 10(76.9) 15(88.2) 33(100.0) 治疗线数 一线治疗 32(40.5) 4(25.0) 3(23.1) 9(52.9) 16(48.5) 5.198 0.158 二线治疗及以上 47(59.5) 12(75.0) 10(76.9) 8(47.1) 17(51.5) 表 5 GC组接受ICI治疗晚期NSCLC患者OS的单因素及多因素分析

变量 参照 单因素 多因素 HR 95%CI P HR 95%CI P 年龄 ≤65岁 1.17 0.72~1.90 0.53 1.13 0.67~1.90 0.658 性别 女 1.23 0.67~2.25 0.502 1.31 0.67~2.55 0.429 吸烟 无 1.34 0.82~2.19 0.250 1.32 0.74~2.36 0.342 病理类型 非鳞癌 1.18 0.74~1.88 0.498 1.04 0.63~1.72 0.885 ECOG评分 0~1分 1.73 1.04~2.88 0.037 1.48 0.85~2.59 0.170 治疗策略 单药 1.02 0.49~2.13 0.966 0.94 0.42~2.14 0.886 治疗线数 一线 1.30 0.79~2.16 0.303 1.23 0.68~2.24 0.499 GC用于非肿瘤相关症状 未用 1.60 0.68~3.72 0.284 1.42 0.59~3.41 0.436 GC用于肿瘤相关症状 未用 4.43 1.90~10.34 0.001 4.18 1.76~9.94 0.001 irAEs 未用 1.31 0.64~2.68 0.463 1.46 0.68~3.11 0.329 化疗前预处理 未用 1.61 0.88~2.93 0.120 1.84 0.96~3.53 0.067 表 6 GC组接受ICI治疗晚期NSCLC患者PFS的单因素及多因素分析

变量 参照 单因素 多因素 HR 95%CI P HR 95%CI P 年龄 ≤65岁 1.17 0.78~1.75 0.462 1.20 0.78~1.86 0.410 性别 女 0.97 0.59~1.59 0.902 0.99 0.57~1.73 0.970 吸烟 无 1.21 0.81~1.83 0.353 1.38 0.83~2.29 0.211 病理类型 非鳞癌 1.08 0.73~1.60 0.713 0.93 0.60~1.45 0.751 ECOG评分 0~1分 1.49 0.97~2.27 0.066 1.24 0.78~1.99 0.361 治疗策略 单药 0.68 0.40~1.17 0.161 0.63 0.34~1.15 0.133 治疗线数 一线 1.38 0.90~2.11 0.138 1.22 0.73~2.05 0.448 GC用于非肿瘤相关症状 未用 1.70 0.87~3.30 0.120 1.56 0.79~3.08 0.200 GC用于肿瘤相关症状 未用 3.17 1.57~6.40 0.001 2.81 1.36~5.81 0.005 irAEs 未用 1.36 0.74~2.49 0.320 1.58 0.82~3.03 0.170 化疗前预处理 未用 1.41 0.85~2.36 0.187 1.68 0.95~2.94 0.073 -

[1] SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGEL R L, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

[2] ZHENG R S, ZHANG S W, ZENG H M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016[J]. J Natl Cancer Cent, 2022, 2(1): 1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002

[3] DUMA N, SANTANA-DAVILA R, MOLINA J R. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and treatment[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2019, 94(8): 1623-1640. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.013

[4] TOPALIAN S L, BRAHMER J R, et al. Five-year survival and correlates among patients with advanced melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, or non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2019, 5(10): 1411-1420. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2187

[5] GARON E B, HELLMANN M D, RIZVI N A, et al. Five-year overall survival for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: results from the phase I KEYNOTE-001 study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2019, 37(28): 2518-2527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00934

[6] SHI T, MA Y Y, YU L F, et al. Cancer immunotherapy: a focus on the regulation of immune checkpoints[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(5): 1389. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051389

[7] 郭怀娟, 杨梦雪, 童建东, 等. 临床药物对免疫检查点抑制剂抗肿瘤效果影响的研究进展[J]. 实用临床医药杂志, 2022, 26(1): 120-122, 133. doi: 10.7619/jcmp.20212975 [8] YANG M X, WANG Y, YUAN M, et al. Antibiotic administration shortly before or after immunotherapy initiation is correlated with poor prognosis in solid cancer patients: an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2020, 88: 106876. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106876

[9] LIU C X, GUO H J, MAO H Y, et al. An up-to-date investigation into the correlation between proton pump inhibitor use and the clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced solid cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 753234. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.753234

[10] CORTELLINI A, TUCCI M, ADAMO V, et al. Integrated analysis of concomitant medications and oncological outcomes from PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2020, 8(2): e001361. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001361

[11] METRO G, BANNA G L, SIGNORELLI D, et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with or without brain metastases from advanced non-small cell lung cancer with a PD-L1 expression ≥ 50%[J]. J Immunother, 2020, 43(9): 299-306. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000340

[12] SAKURADA T, NOKIHARA H, KOGA T, et al. Prevention of pemetrexed-induced rash using low-dose corticosteroids: a phase Ⅱ study[J]. Oncologist, 2022, 27(7): e554-e560. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyab077

[13] LANSINGER O M, BIEDERMANN S, HE Z H, et al. Do steroids matter A retrospective review of premedication for taxane chemotherapy and hypersensitivity reactions[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2021, 39(32): 3583-3590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01200

[14] YOKOE T, HAYASHIDA T, NAGAYAMA A, et al. Effectiveness of antiemetic regimens for highly emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review and network meta-analysis[J]. Oncologist, 2019, 24(6): e347-e357. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0140

[15] YAN Y J, FU J M, KOWALCHUK R O, et al. Exploration of radiation-induced lung injury, from mechanism to treatment: a narrative review[J]. Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2022, 11(2): 307-322. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-22-108

[16] DRAKAKI A, DHILLON P K, WAKELEE H, et al. Association of baseline systemic corticosteroid use with overall survival and time to next treatment in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in real-world US oncology practice for advanced non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, or urothelial carcinoma[J]. OncoImmunology, 2020, 9(1): 1824645. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1824645

[17] MOUNTZIOS G, DE TOMA A, ECONOMOPOULOU P, et al. Steroid use independently predicts for poor outcomes in patients with advanced NSCLC and high PD-L1 expression receiving first-line pembrolizumab monotherapy[J]. Clin Lung Cancer, 2021, 22(2): e180-e192. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.09.017

[18] SVATON M, ZEMANOVA M, ZEMANOVA P, et al. Impact of concomitant medication administered at the time of initiation of nivolumab therapy on outcome in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Anticancer Res, 2020, 40(4): 2209-2217. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14182

[19] FUCÀ G, GALLI G, POGGI M, et al. Modulation of peripheral blood immune cells by early use of steroids and its association with clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors[J]. ESMO Open, 2019, 4(1): e000457. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000457

[20] WU M L, HUANG Q R, XIE Y, et al. Improvement of the anticancer efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade via combination therapy and PD-L1 regulation[J]. J Hematol Oncol, 2022, 15(1): 24. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01242-2

[21] MAEDA N, MARUHASHI T, SUGIURA D, et al. Glucocorticoids potentiate the inhibitory capacity of programmed cell death 1 by up-regulating its expression on T cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2019, 294(52): 19896-19906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010379

[22] QUATRINI L, VACCA P, TUMINO N, et al. Glucocorticoids and the cytokines IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 present in the tumor microenvironment induce PD-1 expression on human natural killer cells[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2021, 147(1): 349-360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.044

[23] YANG H, XIA L, CHEN J, et al. Stress-glucocorticoid-TSC22D3 axis compromises therapy-induced antitumor immunity[J]. Nat Med, 2019, 25(9): 1428-1441. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0566-4

[24] CAIN D W, CIDLOWSKI J A. Immune regulation by glucocorticoids[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2017, 17(4): 233-247. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.1

[25] RHEN T, CIDLOWSKI J A. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids: new mechanisms for old drugs[J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 353(16): 1711-1723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050541

[26] PAULSEN O, KLEPSTAD P, ROSLAND J H, et al. Efficacy of methylprednisolone on pain, fatigue, and appetite loss in patients with advanced cancer using opioids: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2014, 32(29): 3221-3228. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.3926

[27] ARROYO-HERNÁNDEZ M, MALDONADO F, LOZANO-RUIZ F, et al. Radiation-induced lung injury: current evidence[J]. BMC Pulm Med, 2021, 21(1): 9. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-01376-4

[28] CLARISSE D, DE BOSSCHER K. How the glucocorticoid receptor contributes to platinum-based therapy resistance in solid cancer[J]. Nat Commun, 2021, 12(1): 4959. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24847-6

[29] SUZUKI K, MATSUNUMA R, MATSUDA Y, et al. A nationwide survey of Japanese palliative care physicians' practice of corticosteroid treatment for dyspnea in patients with cancer[J]. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2019, 58(6): e3-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.08.022

[30] DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULD J, NOËL N, LAMBOTTE O. Management of immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients: a patient-centred approach[J]. Intern Emerg Med, 2020, 15(4): 587-598. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02295-2

[31] RICCIUTI B, DAHLBERG S E, ADENI A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor outcomes for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer receiving baseline corticosteroids for palliative versus nonpalliative indications[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2019, 37(22): 1927-1934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00189

[32] SKRIBEK M, ROUNIS K, AFSHAR S, et al. Effect of corticosteroids on the outcome of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2021, 145: 245-254. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.12.012

[33] DE GIGLIO A, MEZQUITA L, AUCLIN E, et al. Impact of intercurrent introduction of steroids on clinical outcomes in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients under immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICI)[J]. Cancers, 2020, 12(10): 2827. doi: 10.3390/cancers12102827

-

期刊类型引用(13)

1. 张少珂. 乳腺X线摄影与磁共振成像对乳腺癌的诊断价值. 影像研究与医学应用. 2024(01): 154-157 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 马强. MRI增强扫描与钼靶成像在诊断乳腺导管原位癌(DCIS)中的应用价值. 中华养生保健. 2024(06): 180-183 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 刘传奇,王洁茹,谢一帆,夏合旦·吾甫尔江,冷晓玲,葛妍. 常规超声、超声萤火虫技术与X线钼靶摄影对乳腺导管原位癌的诊断价值. 癌症进展. 2023(04): 380-383 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 李新建. 钼靶X线与磁共振对乳腺疾病的诊断价值. 影像研究与医学应用. 2023(07): 167-169 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 张晓华,魏战友. 超声和钼靶X线检查对更年期女性乳腺微小肿块的诊断比较. 影像科学与光化学. 2022(04): 868-872 .  百度学术

百度学术

6. 孙卫平. 高频彩超及X线钼靶检查对乳腺原位癌早期诊断作用分析. 影像研究与医学应用. 2022(15): 134-136 .  百度学术

百度学术

7. 李志湄,刘业培,焦洪斌. 钼靶DR摄影联合DCE-MRI在乳腺肿块良恶性鉴别中的应用价值. 中国医疗设备. 2022(10): 79-82+100 .  百度学术

百度学术

8. 吴丽萍,张南,刘文霞. 乳腺癌磁共振参数与表皮生长因子受体2增殖细胞核抗原相关性. 河北医学. 2022(10): 1684-1689 .  百度学术

百度学术

9. 李旭华,陈玉兰,赖芳. 不同病理特征乳腺导管原位癌患者的微浸润情况与影响因素. 数理医药学杂志. 2022(12): 1788-1791 .  百度学术

百度学术

10. 宋倩,刘景萍,冯华梅,聂维齐,王泱. 乳腺导管内癌的病理特征与钼靶X线摄影及超声造影检查的相关性. 实用临床医药杂志. 2021(13): 28-31 .  本站查看

本站查看

11. 孙妮旎,邱霞,王晓青. 体表交叉结合乳腺X线立体导丝定位在切除乳腺钙化灶中的应用. 浙江创伤外科. 2021(05): 867-869 .  百度学术

百度学术

12. 罗珺,李庆福,陈常群,范波,李照星. 全数字化乳腺摄影联合数字乳腺断层摄影对乳腺病变及乳腺钙化的诊断价值. 实用临床医药杂志. 2021(22): 5-9 .  本站查看

本站查看

13. 沐玮玮,李海歌. 3.0T磁共振与乳腺钼靶摄影对乳腺癌诊断的临床价值. 影像研究与医学应用. 2020(20): 65-67 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

下载:

下载:

苏公网安备 32100302010246号

苏公网安备 32100302010246号